Cover Story

“One Dance” returns to the stage after selling out three performances at the Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater in New York, two years ago. The latest and greatest iteration of this modern reinterpretation of traditional Korean dance will soon appear before audiences.

2년 전 미국 뉴욕 링컨센터 데이비드 H 코크 극장에서, 공연 3회차의 전석을 매진시켰던 ‘일무’의 막이 다시 열린다. 한국 춤의 전통을 현대적으로 재해석한 ‘일무’가 한 발 더 진보한 모습으로 관객을 찾는다.

Writer. Sung Ji Yeon

Photos courtesy of. Sejong Center

The Pinnacle of Korean Performing Arts

“One Dance (called Ilmu in Korean)” is inspired by Ilmu, the choreographed component of Jongmyo Jeryeak (royal ancestral ritual music at the Jongmyo Shrine), which is recognized as an intangible cultural heritage both by the Korean government and by UNESCO. Jongmyo Jeryeak consists of the instrumental music, songs and dances performed in the ceremonies for the deceased kings and queens of the Joseon Dynasty whose spirit tablets are enshrined at Jongmyo. In particular, the dances are ensemble performances in which rows of dozens of dancers move in energetic unison, as if parts of a single organism.

“One Dance” was created in 2022 under the lead of creative director and designer Jung Ku-ho. Each element of the performance—the costumes, stage design, lighting, choreography and music—was crafted according to Jung’s guiding philosophy of minimalism. The clothing was redesigned, and the choreography rearranged to fit together seamlessly. To encompass all aspects of the performance, Jung designed the stage to be plain but still capture viewers’ attention.

Those efforts culminated in “One Dance,” which has been regarded since its debut in 2022 as a quintessential expression of Korean aesthetics that demonstrates the untapped potential of Korean dance. This article explores its captivating appeal to viewers.

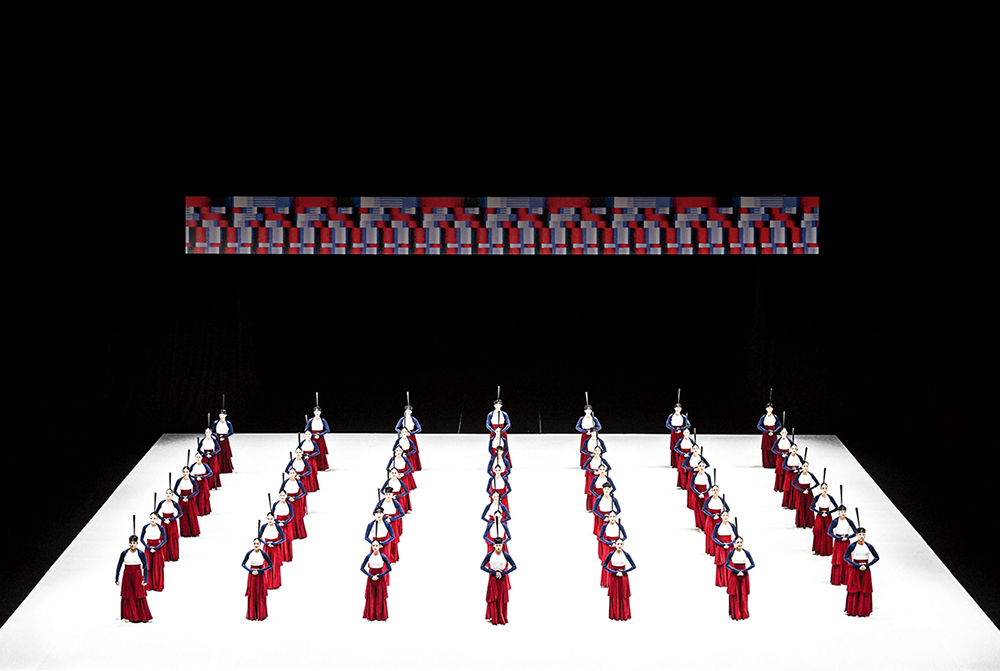

A scene from Act 4 Sin-Ilmu

Tradition in Transition

One theme running throughout “One Dance” is that tradition is always changing. Over the four acts of the performance, audience members find themselves wondering why these changes are necessary, but to appreciate them more fully, you need to focus on the flow of the dance—on the auditory and visible changes that occur from one scene to another and from one act to another.

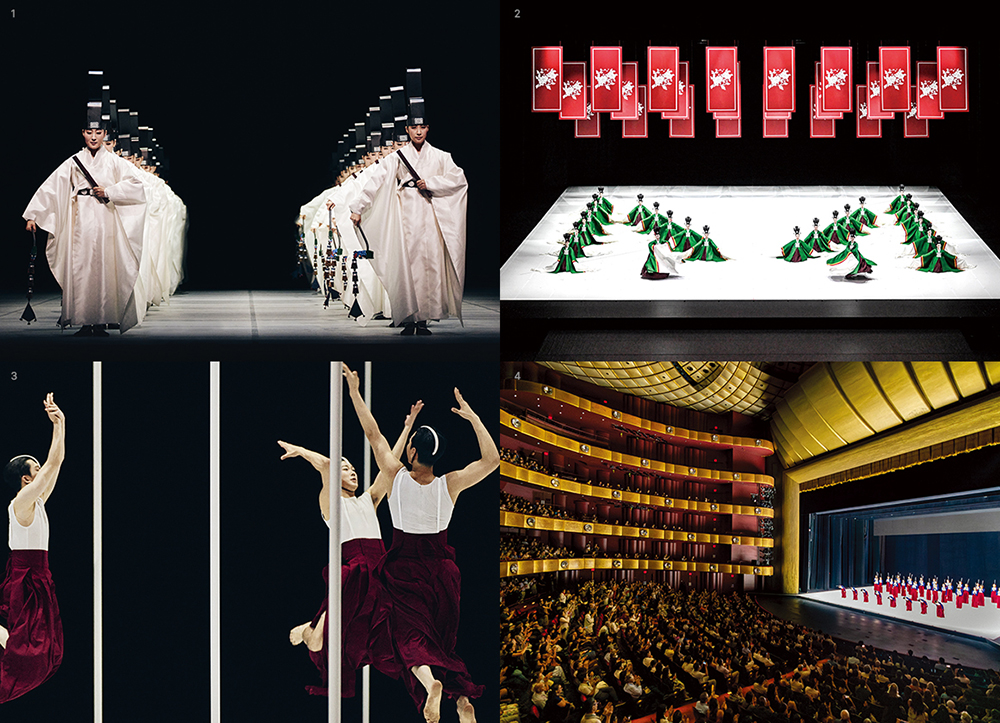

The Munmu dance in Scene 1 of Act 1 is performed to a song praising the king’s wisdom, while the Mumu dance in Scene 3 is performed to a song honoring the king’s military exploits. Both are slow dances that generally involve upper body movement, unlike the dynamic movements seen in today’s pop choreography or the emotions they express. But there’s something solemn about the uniform movements that the dancers pull off flawlessly. Combined with the majestic music, the dance evokes the sublimity of a religious ceremony.

A scene from Act 1, Study of Ilmu

The second and fourth scenes add variation to the dance found in the first and third. As the original formation goes through several transformations, columns of dancers move together to delineate hulking shapes, while their limbs don’t move with the rapidity of synchronized dance in K-pop today. One column may depict a circle or stand in line, with each dancer slashing downward, one after the other.

The Chunaengmu dance of Act 2 is arranged in a similar fashion. This dance was created during the reign of Sunjo of Joseon by Crown Prince Hyomyeong for his mother Queen Sunwon. The original dance envisioned a single woman taking the stage and moving very little. But in the first scene of this act, the single-person Chunaengmu expands into a group dance. Beginning with a duo on stage, the performance gradually expands to 24 dancers. In the second scene, the dancers’ movements grow freer and more fanciful as they undulate their shoulders, lift their legs, and move into a formation resembling a flower.

Through Act 2, the performance alternates between close reproductions and reinterpretations of the traditional dances. Just as audience members are perceiving how Korean dance has changed over the years, Act 3 lands with an invitation to contemporary Korean dance. Based on traditional techniques, 54 dancers present totally original choreography, unlike the traditional reproductions and reinterpretations of the first two acts. This is a male group dance performed using long poles amidst numerous bamboo installations.

The fourth and final act features Sin-Ilmu (meaning new Ilmu), embodying the concept of “neo-tradition” through a fresh interpretation of the meaning and aesthetics behind Ilmu’s music, choreography and fashion. The rhythm of the music gradually accelerates, driven by a suite of percussion instruments. The varying movements of the dancers are quick and lively, and their elegant choreography gives way to scenes of explosive power.

1.Act 1, Study of Ilmu

2. Act 2, Study of Gungjungmu

3. Act 3, Jukmu

4. A performance of 'One Dance' at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center, New York, in July 2023

Tunes and Treads, Reinterpreted

The reinterpretation of tradition in “One Dance” goes beyond choreography. The music, attire and mise-en-scène all represent a new interpretation of tradition. The music starts out with traditional instruments playing pieces inspired by Jongmyo Jeryeak before shifting to contemporary instruments such as contrabass, bass and singing bowls. Interestingly, the Western instruments are adjusted to produce a timbre similar to traditional Korean instruments. The mood is lightened by dropping the taepyeongso (double-reed wind instrument) and a few other instruments, and the rhythm is gradually made more elaborate to add novelty to the traditional foundation, underpinning the “reinterpretation of tradition” that is the theme of “One Dance.”

Something similar is done with the attire. The outfits worn in Act 1, while being unmistakably Hanbok (Korean traditional clothing), don’t follow the old forms exactly. The outfits in the Munmu dance are redone in white, while the burgundy typically seen in the Mumu dance is swapped out with orange, which is visually sharper and more vibrant. The gwanmo headgear is embellished with feathers. Its shape is boldly and dramatically altered, and the sleeves are broadened to highlight the dancers’ movements. The clothing worn during the Chunaengmu dance in Act 2 is designed to be blue when the dancers are still but show white when the arms are raised and red when the legs are raised, highlighting the changes on stage. By the time we reach Sin-Ilmu in Act 4, accessories have disappeared, and the outfits have become simple. Red skirts, white blouses and blue jackets evoke the Korean flag, known as the Taegeukgi. These final outfits have strong, structured lines that maintain a sleek silhouette, enhancing the impression of agility.

While every element of “One Dance” has a distinctly modern touch, audience members are apt to view it inside the overarching concept of tradition. So it’s only after they’ve viewed the full narrative—when Act 4 rolls around—that they begin to grasp the meaning the show seeks to convey. They’re also encouraged to reflect upon the necessity of contemporary interpretations of tradition that are exemplified by “One Dance.”

The performance that was highly praised by dancer Alex Wong, “Lion King” musical director Julie Taymor, and respected theater critic Roma Torre and described in the international press as an unforgettable 70 minutes during its 2023 run in New York is your perfect opportunity to discover a new side of the Korean dance scene.