Story

Korea’s Culture of Play

- Written by Hwang Ji Hae

researcher at the Cultural Heritage Administration

From Communal Games to Online Games, Play Brings Koreans Together

From folk games and alley games to board games and online games, Korea’s culture of play has evolved over time. Though outward expressions have changed, Korea’s culture of play is still grounded in a sense of community and the value of togetherness.

In his 1938 book “Homo Ludens,” the Dutch cultural theorist Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) issued the epoch-making opinion that play was not merely a factor of culture, but culture itself. Rather than defining play as subordinate to culture, as previous theories had, Huizinga claimed that culture actually sprang from play.

‘Squid Game’ and Play

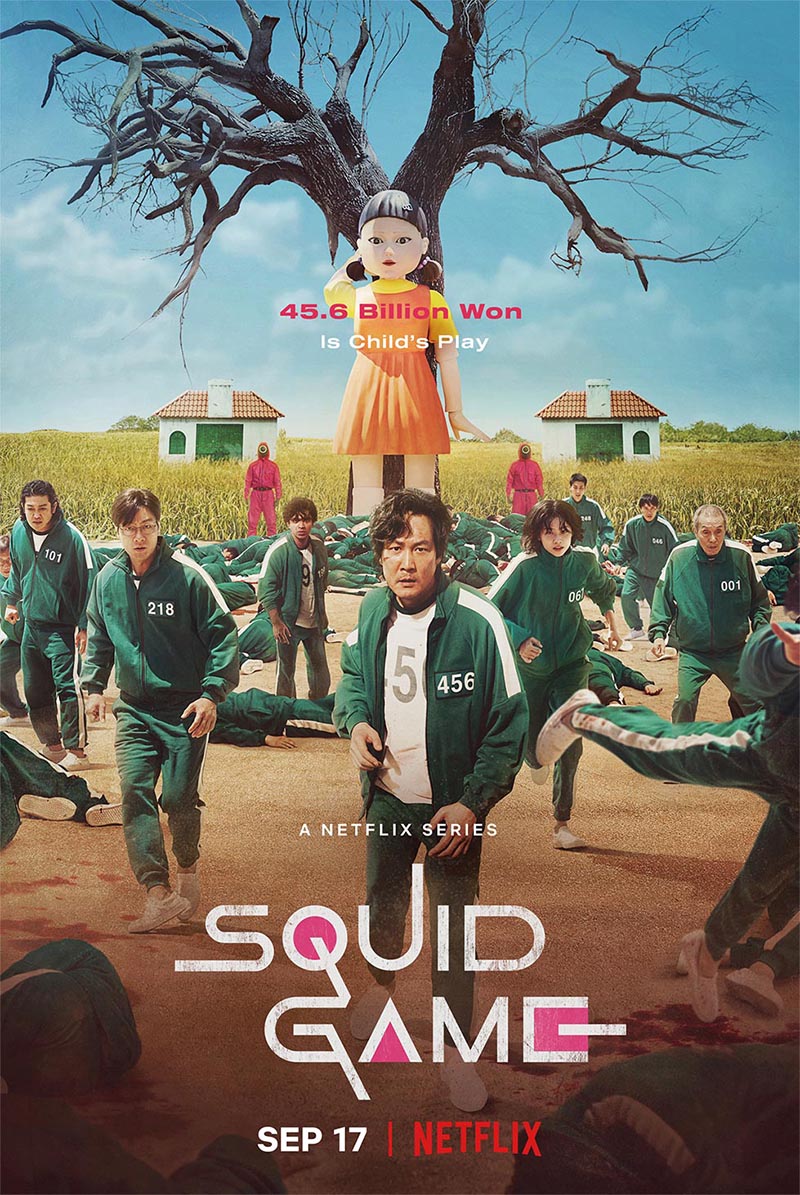

About 80 years after Huizinga published his study, the first academic look at play, the world is now fixed on the TV series “Squid Game.” The most popular Netflix TV series worldwide of 2021, the Korea-produced “Squid Game” has had quite the cultural impact. The games that appear in the show have become global fads, while parody material has quickly spread through social media.

Have Korean games ever before garnered such intense global interest? We once again feel the reality of Huizinga’s claim that “[play] does not come from play like a baby detaching itself from the womb: it arises in and as play, and never leaves it.”

The hit Netflix series “Squid Game” has brought global attention to the Korean games that appear in the show. © Netflix

Community and the Tug-of-War

In “Squid Game,” the tug-of-war demonstrated extreme tension, excitement and the beauty of strategy. The game boasts such heritage and significance that the “tugging rituals and games” of Korea, Cambodia, the Philippines and Vietnam were inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2015.

The tug-of-war is a representative “community game,” with a village traditionally divided into two teams and everyone taking part regardless of age or sex. Teams pull a giant rope to which smaller ropes have been attached to a larger one, with anywhere from 100 people to a thousand taking part.

The two halves of the rope are defined as the “male” and “female” sides, and Koreans traditionally consider the fusion of the two and the pulling of the rope to be an act of sexual union. The game embodies the homeopathic magic where villagers pray for happiness and a rich harvest. Sparring against one another is hugely fun, but everyone enjoys the tug-of-war no matter who wins, a reflection of the game’s ritualistic nature as a prayer for peace and abundance. To achieve this common goal, villagers jointly take part in the game, working together with their neighbors.

In fact, villages rarely hold a tug-of-war on its own. They usually host them around the time of the Jeongwol Daeboreum (day of the first full moon of the lunar year). The villagers typically offer prayers for peace and prosperity to the village’s guardian deity, play percussion music to drive out evil spirits from each home and then, finally, play tug-of-war.

Not only the tug-of-war, but any game in which entire villages take part function to strengthen social unity and cohesion; they also have a magical ability to grant abundance and village prosperity. Even today, a tug-of-war is frequently held on holidays or by companies, schools or alumni associations to promote unity, as well as for fun. The long-held community spirit of Koreans continues to play a positive role in many ways through play, even in modern society.

Students take part in a tug-of-war. © Yonhap News

Children’s Alleyway Games and Family Board Games

In Korea’s heritage of play, the alleyway is the recent past itself. This is because play lies at the heart of the alleyway. As the exclusive space of local children, the neighborhood alleyway performed the role of growing space, where children could grow through play. To adults as well, alleyways are a precious space embodying memories of youth that awaken childlike innocence, so much so that alleyway tours have recently become popular.

Children lost track of time playing games such as Red Light, Green Light, marbles, tag and hopscotch. During the period of industrialization around the time of the Korean War, Chinese jump rope, ddakjichigi (slap match), the “squid game,” paper fortune-telling and gunsa nori (military game) were added to the mix. Children chose games according to the number of players gathering in the alleyway, and gradually grew into adults as they ran the rules of the games. When friends gathered, they could have fun playing games in the alleyway or courtyard with just a few marbles, a rubber rope or a few stones. No Legos or computers were needed.

People living on islands in the southwestern part of the country used freshly-caught fish in their kimchi. The lactic acid bacteria and functional materials produced in the kimchi’s natural fermentation process removes putrefactive and harmful bacteria. In fact, people in this region placed kimchi in between lettuce leaves along with freshly-caught fish to ferment it. When the kimchi completed its fermentation process, the fish was taken out, sliced and eaten along with the kimchi; this is why kimchi was considered a great side dish.

Alleyway games fell significantly out of favor due to accelerated development in the 1970s and the rapid proliferation of apartments, but children continue to grow playing alleyway games in schoolyards and parks.

© gettyimage

© gettyimage

Typical indoor children’s games such as gonggi (Korean-style jacks), the string game and rock, paper, scissors were joined in the 1970s by Korea’s first board game Baemjusawi (a local version of Snakes and Ladders). The game “Blue Marble,” launched in 1982, was so popular that it transformed Korea’s indoor game scene. Board games involving strategy really suited Korean children, who were used to playing the traditional game yunnori, a board game involving sticks rather than dice. Board games also compared well to yunnori in that entire families could gather to play. Until the 2000s, when foreign board games began entering the country in earnest, Blue Marble was the “people’s game,” the champion of Korea’s game scene.

Online Homo Ludens

In Korea, as elsewhere, online play through online games, YouTube and other means has become commonplace. Place, participants and game type no longer seem important to people of today. You can play anywhere, anyone can take part, and you can play whichever game you like. The most important value is “playing together.” The games of the past, games of the present and games of the future inevitably share that they connect people. This is just as we’ve seen with the Korean games that appeared in “Squid Game,” which have gone on to become a “culture of play” enjoyed by people all over the world. As an online community, we are also “online home ludens.”

Online games continue the tradition of playing “together.” © Imagetoday